Johannes

Stahl

CAPITAL

AND CAPUT

OR COMING TO TERMS WITH A CENTRAL DILEMMA

It

is general knowledge that the term "capital" is derived from "caput",

the latin word for head. Any attempts at an interpretation based on other associations

- the Roman Capitol, Marx's DAS KAPITAL, capital punishment, capital gains tax

etc. - are simply heading for trouble. There are a Iot of different things beginning

with "head" - in fact too many for comfort.

The

title-page of Thomas Hobbes

"leviathan'" - in many respects quite remarkable - transposes this

verbal equation into a vivid image. In order to bring home his absolutist theory

of government to non-readers or to people who can think better in pictures than

in words, Hobbes depicts the state as a human organism. And there is absolutely

no doubt as to who the head is meant to be. However, it would perhaps be going

too far to translate this metaphor of the body politic into city-planning terms

or to instigate typological studies in this direction ,

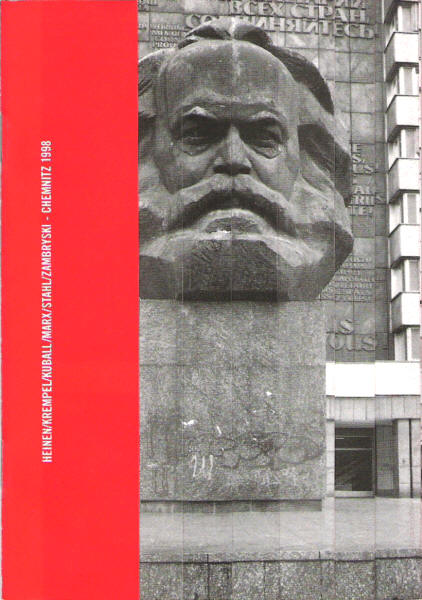

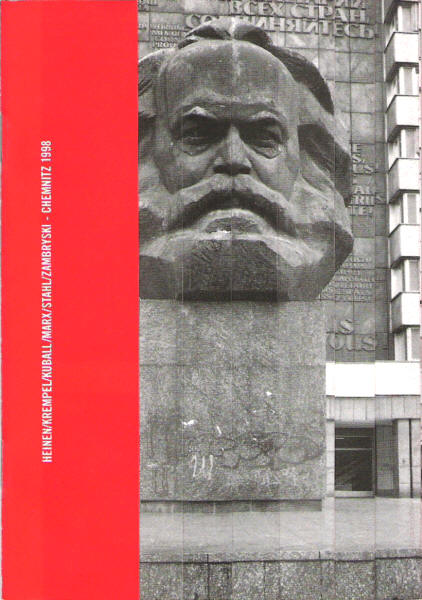

especially when the head in question is a bronze sculpture which stands in the

middle of what used to be called "Karl-Marx-Stadt". On the other hand,

there have been frequent attempts in the past at interpreting this central urban

complex as the outward expression of socialist ideology. If this is a problem,

then it is one which primarily concerns the preservation of monuments and, as

such, is also one of historical and political identity.

What

aggravates this problem additionally, however, is the city architecture whithin

the immediate surroundings of the monument. But for the occasional historical

gem - the "Schloßplatz" being one example - the "Straße

der Nationen" is flanked by that typical monotonous architecture which

was celebrated all over East Germany (in Magdeburg, Dresden and Eisenhüttenstadt,

for example) as the ultimate achievement of socialist architecture and of the

social idea behind it: the complete intermeshing of living and working environments,

The buildings that line the main street of Chemnitz not only clearly reveal

their practical function but also show what a state-run working and living community

can look like in our industrial age. Similar complexes - born either of related

or even of like-minded ideologies - were also built in Frankfurt am Main and

in other cities of West Germany.

What is peculiar to the Chemnitz situation, however, is the relationship between

the huge head of Karl Marx and the main street. Like all the other squares along

the street, the head simply "docks" onto it. Being the most recent

sequel in the history of the city, the head claims the right to write the last,

valid chapter of Chemnitz's history book and, in so doing, to embody the city's

new name in a chronicle made physically visible by its architecture and city

planning. This huge, neckless head cannot fail to have achieved its monumental

effect. As a virtually architectural solution to the problem of building a sculpture

of such huge dimensions, it certainly affords some scope for innovation in formal

terms, though its figuration and its political message clearly belong to the

period of its origin and to the historicizing

attitudes which prevailed at that time.

What

aggravates this problem additionally, however, is the city architecture whithin

the immediate surroundings of the monument. But for the occasional historical

gem - the "Schloßplatz" being one example - the "Straße

der Nationen" is flanked by that typical monotonous architecture which

was celebrated all over East Germany (in Magdeburg, Dresden and Eisenhüttenstadt,

for example) as the ultimate achievement of socialist architecture and of the

social idea behind it: the complete intermeshing of living and working environments,

The buildings that line the main street of Chemnitz not only clearly reveal

their practical function but also show what a state-run working and living community

can look like in our industrial age. Similar complexes - born either of related

or even of like-minded ideologies - were also built in Frankfurt am Main and

in other cities of West Germany.

What is peculiar to the Chemnitz situation, however, is the relationship between

the huge head of Karl Marx and the main street. Like all the other squares along

the street, the head simply "docks" onto it. Being the most recent

sequel in the history of the city, the head claims the right to write the last,

valid chapter of Chemnitz's history book and, in so doing, to embody the city's

new name in a chronicle made physically visible by its architecture and city

planning. This huge, neckless head cannot fail to have achieved its monumental

effect. As a virtually architectural solution to the problem of building a sculpture

of such huge dimensions, it certainly affords some scope for innovation in formal

terms, though its figuration and its political message clearly belong to the

period of its origin and to the historicizing

attitudes which prevailed at that time.

The

way the sculpture relates to the extensive frontage against which it has been

placed is reminiscent of the effect often achieved by a sculpture in relation

to the walls of the room in which it is exhibited. The idea that a free-standing

sculpture may relate not only to the architecture behind it but also bear a

defined and political relationship to the place where it has been erected is

not new as such. What is Karl Marx's head in Chemnitz is the Roland statue in

Bremen, or any one of the countless equestrian statues that stand in front of

the buildings from which political power was at one time wielded. Whilst enough

has certainly been thought and said about the political differences, it is still

worth our while to give some thought to the formal aspects of this sculpture.

What is noticeable first and foremost is the fact that the head and the frontage

of the building behind it form an integral whole in terms of scale, form and

content. Particularly remarkable, too, is the heavily emphasized frontality

of the sculpture; the possibility of viewing the sculpture at an angle or in

profile is definitely subordinate to the full frontal view. From the front,

the head can be readily viewed by pedestrians at street level - the eyes of

the sculpture are directed straight at them - and also from a more distant stand

point where the striking, optical attributes of Marxism are just as easily discernible.

No doubt these different possible viewing distances account for the various

differently sized inscriptions on the sculpture. Whilst the monumentality of

the entire complex is obvious, one question still remains: Is the scale of the

sculpture in keeping with the similarly large-scaled architecture of the city?

The question is altogether valid if we think of Thomas Hobbes' title-page.

Moreover,

the head is mounted not just on a double plinth but also on a large step which

raises the entire sculpture above the level of the street. Whilst the reasons

for this may have lain not just in the desire to express monumentality but also

in the very pragmatic need for a proportionate relationship with the background

architecture, the plinth and the step do in fact make a formal contribution

- and with absolutely classic means - towards a heightening of content. It is

precisely in this regard that a comparison with Hubertus von Pilgrim's "Adenauer

Head" - a subsequently executed and, in artistic terms, altogether unhappy

sculpture outside the Chancellor's Office in Bonn - would be helpful.

The

situation is unique - perhaps because it is as valid as it is anachronistic.

This combination of the architectural individuality of the complex as a whole

and the lack of individuality in the formal, sculptural detail of the monument

itself runs counter to existing, meanwhile complacent patterns of thought and

suppression. Artistic intervention will obviously be the most suitable means

of resolving this dilemma between city planning, form and idea, between the

head and its city.

Johannes

Stahl

What

aggravates this problem additionally, however, is the city architecture whithin

the immediate surroundings of the monument. But for the occasional historical

gem - the "Schloßplatz" being one example - the "Straße

der Nationen" is flanked by that typical monotonous architecture which

was celebrated all over East Germany (in Magdeburg, Dresden and Eisenhüttenstadt,

for example) as the ultimate achievement of socialist architecture and of the

social idea behind it: the complete intermeshing of living and working environments,

The buildings that line the main street of Chemnitz not only clearly reveal

their practical function but also show what a state-run working and living community

can look like in our industrial age. Similar complexes - born either of related

or even of like-minded ideologies - were also built in Frankfurt am Main and

in other cities of West Germany.4

What is peculiar to the Chemnitz situation, however, is the relationship between

the huge head of Karl Marx and the main street. Like all the other squares along

the street, the head simply "docks" onto it. Being the most recent

sequel in the history of the city, the head claims the right to write the last,

valid chapter of Chemnitz's history book and, in so doing, to embody the city's

new name in a chronicle made physically visible by its architecture and city

planning. This huge, neckless head cannot fail to have achieved its monumental

effect. As a virtually architectural solution to the problem of building a sculpture

of such huge dimensions, it certainly affords some scope for innovation in formal

terms, though its figuration and its political message clearly belong to the

period of its origin and to the historicizing

attitudes which prevailed at that time.

What

aggravates this problem additionally, however, is the city architecture whithin

the immediate surroundings of the monument. But for the occasional historical

gem - the "Schloßplatz" being one example - the "Straße

der Nationen" is flanked by that typical monotonous architecture which

was celebrated all over East Germany (in Magdeburg, Dresden and Eisenhüttenstadt,

for example) as the ultimate achievement of socialist architecture and of the

social idea behind it: the complete intermeshing of living and working environments,

The buildings that line the main street of Chemnitz not only clearly reveal

their practical function but also show what a state-run working and living community

can look like in our industrial age. Similar complexes - born either of related

or even of like-minded ideologies - were also built in Frankfurt am Main and

in other cities of West Germany.4

What is peculiar to the Chemnitz situation, however, is the relationship between

the huge head of Karl Marx and the main street. Like all the other squares along

the street, the head simply "docks" onto it. Being the most recent

sequel in the history of the city, the head claims the right to write the last,

valid chapter of Chemnitz's history book and, in so doing, to embody the city's

new name in a chronicle made physically visible by its architecture and city

planning. This huge, neckless head cannot fail to have achieved its monumental

effect. As a virtually architectural solution to the problem of building a sculpture

of such huge dimensions, it certainly affords some scope for innovation in formal

terms, though its figuration and its political message clearly belong to the

period of its origin and to the historicizing

attitudes which prevailed at that time.